Interviewer & Compiler: Aidan Mao, Grade 12 Student from St Robert Catholic School, Robotics Captain

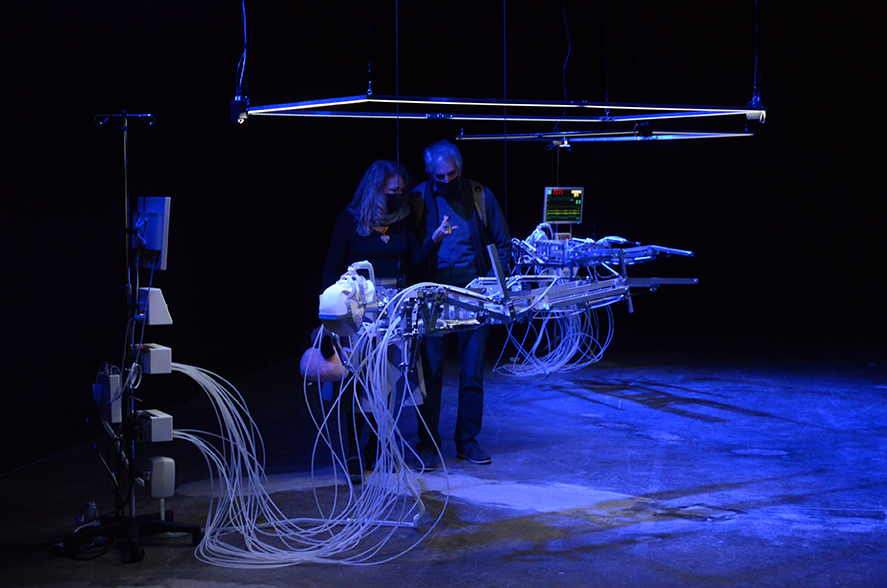

ICU (Intensive Care Unit), 2021, Photo: © Bill Vorn

Introduction

I am a Grade 12 student and captain of Team 7520 in the FIRST Robotics Competition. For the past few years I have been building large-scale robots that compete on the world stage. Robotics has taught me engineering skills, teamwork, creativity, and persistence. At the same time I have become more curious about how robotics can cross into art, how machines can move beyond function to provoke emotion and thought.

To explore this intersection, I interviewed Bill Vorn, one of the world’s leading robotic artists. Based in Montreal, he has been creating robotic installations since the early 1990s that combine pneumatics, programming, sound, and light to immerse viewers in environments where machines behave in ways that feel uncannily alive. His groundbreaking projects, such as La Cour des Miracles and Inferno, have been exhibited internationally in major festivals and galleries, influencing generations of artists working at the crossroads of technology and performance.

Vorn recently retired from his position as professor in Concordia University’s Department of Studio Arts, where he taught electronic arts, robotic art, and interactive systems for many years. His career bridges performance, engineering, and philosophy, often exploring empathy for machines, the aesthetics of dysfunction, and the line between human and mechanical behavior.

For me, it was inspiring to speak with someone who has devoted decades to this field, long before robotics became a common cultural subject. What follows is a transcript of our discussion, edited lightly for clarity but keeping his words as original as possible.

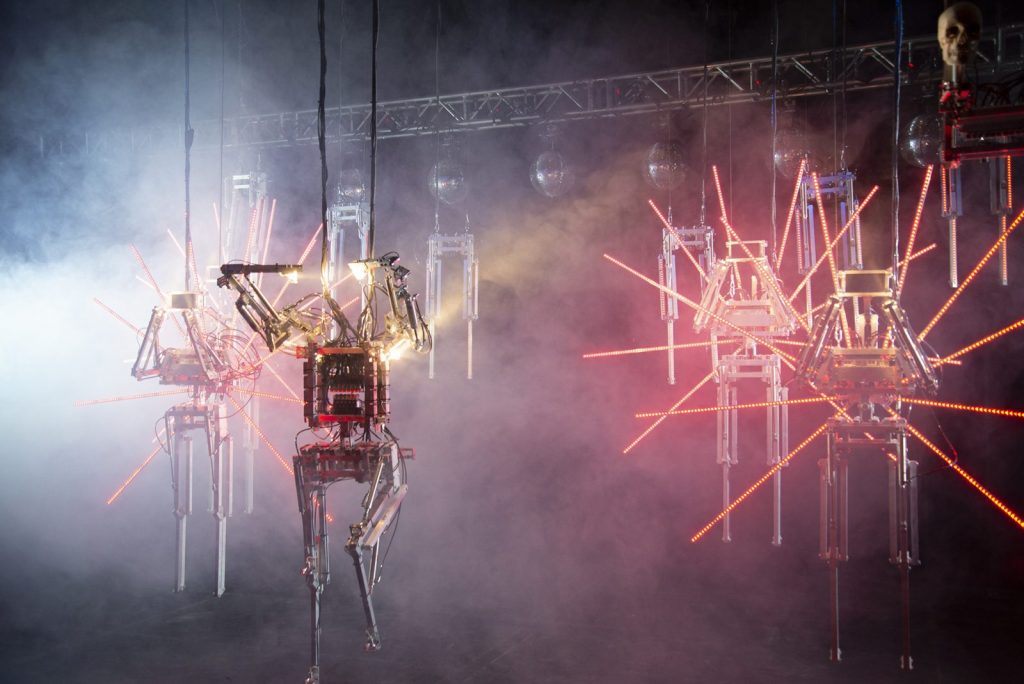

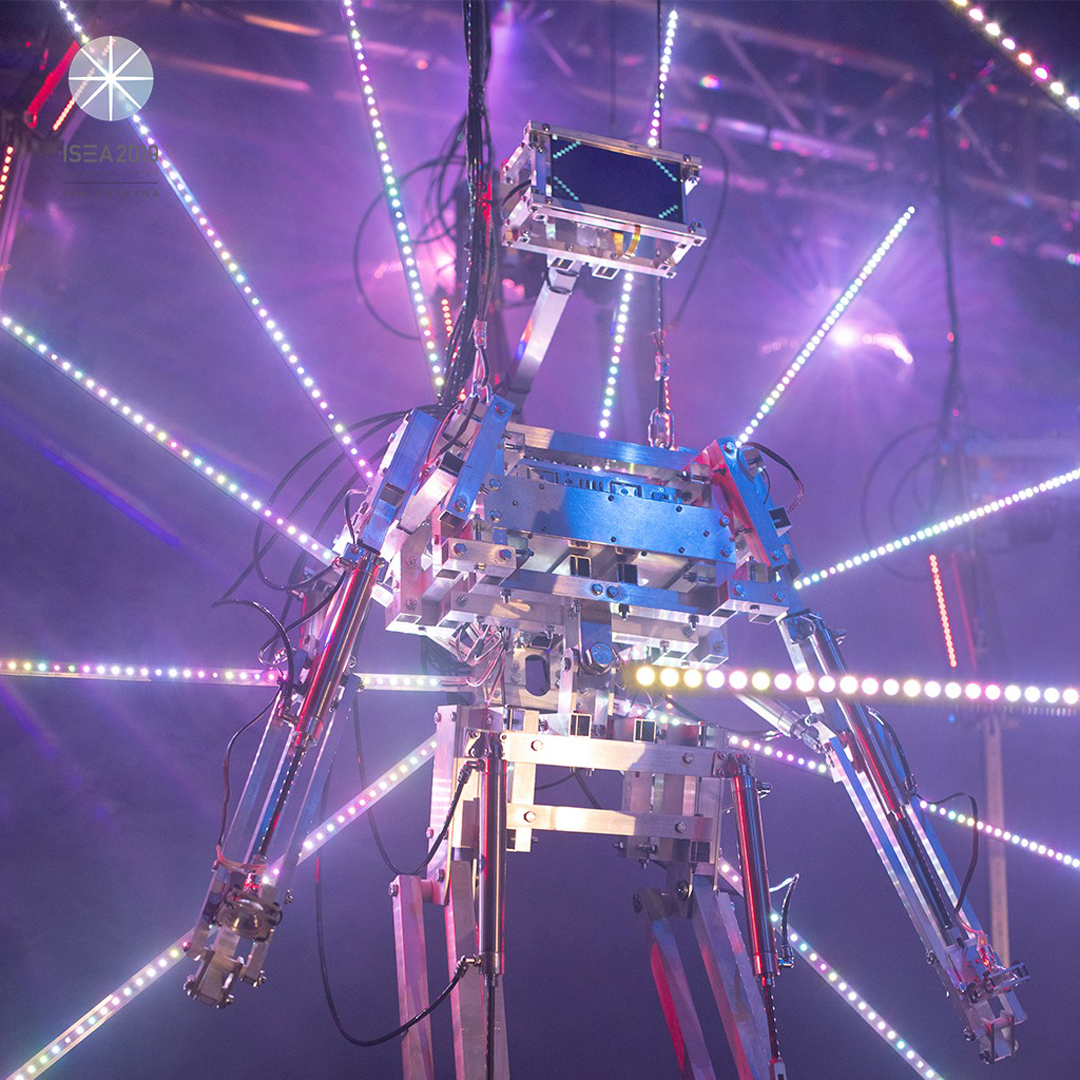

Copacabana Machine Sex, 2018. Performance robotique. Photo: © Bill Vorn

Q: You have so many skills — music, robotics, visual art. Why did you choose to be an artist instead of an engineer?

Bill Vorn: I was an artist first. I started with electronic music. Robotics came later as an extension of that. For me, the main thing is creating a good show, not just solving technical problems. I enjoy engineering challenges, but what interests me most is the impact I can have on an audience.

I studied communication, which is not exactly science or art but a bit of both. That background pushed me to integrate electronics, programming, sound, lighting, and staging into one practice.

Q: What do you want audiences to feel when they experience your shows?

Vorn: It depends on the work. In 1997 we created La Cour des Miracles, inspired by Victor Hugo. It was a space where machines looked imperfect, like something was wrong or they were in pain. The goal was to provoke empathy for machines. Sometimes people even cried.

Other projects are different. In Inferno, participants wear exoskeletons that control their movements. In that case it is not about feeling for machines but about becoming one, experiencing what it is like to have your body taken over.

So the feelings vary: empathy, immersion, fear, spectacle. But the point is always to create a strong reaction.

Q: You started robotic art in the early 1990s, before robotics was common in art. How was that?

Vorn: We were not the first. In the United States some artists did robot performances in the 1980s. But in the early 1990s it was still unusual. In Europe people were more open-minded than in America. Festivals there were happy to present robotic performances, while in the U.S. it was harder to find space for them.

So yes, it felt new, especially because we did not have many references. We were figuring things out as we went.

Immersive robotic installation La Cour des Miracles 1997 [55]. ©Bill Vorn & Louis-Philippe Demers

Q: Why robots? Why did you choose them as your medium?

Vorn: Movement. At first I worked with sound, and then I made speakers that physically moved in space. That made me curious about machines that move in other ways.

Our first robots were abstract prototypes used in groups. Later they became more anthropomorphic, first animal-like and then more human-like, with legs, arms, or heads. They never looked realistic, but they suggested life.

As soon as you see something move, you start projecting emotions onto it. That projection is automatic, and I find it fascinating.

Q: When you design a new piece, do you start from a technical idea or a concept?

Vorn: Both, depending on the project. Sometimes I start technically, like experimenting with pneumatics or soft robotics. Other times I start with a theme, like misery in La Cour des Miracles or mental disorders in another project based on the DSM.

Often ideas sit for years before the right time or tools come to realize them.

Q: What hardware and software do you usually use?

Vorn: Hardware: mostly pneumatics, pistons, valves, and compressed air. They are reliable, which is important for shows that last months. I also use motors, servos, and steppers, but pneumatics are my favorite.

I build with aluminum because it is strong, light, and easy to machine. I also use plastics like Delrin for joints.

Software: my main platform is Max/MSP, which controls everything, including sound, light, video, haze, and microcontrollers. From there I connect to Arduinos, Raspberry Pis, ESP32s, and custom controllers. It depends on what each project needs.

Q: In robotics, glitches happen a lot. Do they ruin your shows, or do you work them in?

Vorn: Usually they just become part of the performance. As long as the glitch does not kill the whole show, it does not matter. With all the elements we use, like lights, sound, and movement, if one thing misbehaves it is just one detail among thousands.

Q: Your works often look raw, uncanny, even dystopian. Why lean into that style?

Vorn: It is an aesthetic choice. I like raw machine aesthetics: visible pistons, tubing, and aluminum. I do not want mannequins or realistic replicas.

For me, machines look alive because of how they move and behave, and because of the environment, including sound, lighting, and atmosphere. With those theatrical tools, raw metal becomes a character.

INFERNO (Demers / Vorn), 2015, Robotic Art Performance, Photo: Magalie Fonteneau @ Stereolux

Q: Do you use AI in your works?

Vorn: Not really. Sometimes for writing text, but my robots do not use AI for behavior. If they did, maybe they would seem more sentient, but AI today is limited. It is based on statistical analysis of data, and the more data you have, the better it works.

That is why tools like ChatGPT are powerful, because they have huge datasets. But in small robots, without that scale, AI is still very narrow. I prefer to focus on motion and human projection. My robots, even though they are always on some form of network, are not connected to the internet in any way (at least not for the moment).

Q: How important is the audience in your work? Do you see them as co-performers?

Vorn: Sometimes, yes. In Inferno the audience literally wears the robots. Without them, the piece does not exist.

Even in installations, the audience matters. Their presence triggers the machines’ behaviors. I often compare building robots to composing music: you do it for yourself, but also for others. You have to imagine the visitor’s perspective.

Copacabana Machine Sex, 2018. Performance robotique. Photo: © Bill Vorn

Q: If you could go back to being a student, what would you do differently?

Vorn: I would have learned 3D modeling much earlier. I only started with CAD in my fifties. Now it’s essential. With CNC machines and 3D printers, I can design and fabricate precisely. Back then, everything was hand-drilled and rough.

Modern tools don’t save much time, but they produce much higher quality. And they let me test ideas quickly.

Q: Where do you draw inspiration from?

Vorn: When I was young, science fiction, books, movies, and comics were huge for me. Today it is more diffuse: exhibitions, documentaries, and things I see at the zoo.

I try not to be influenced by social media. My work is less about imagining the future and more about reacting to the present. Critics sometimes say my pieces look like science fiction, but for me they are about machines as they exist today.

Q: What happens to your robots after a project? Do you keep them, recycle them into new works, or even keep them around as decorations?

Vorn: A bit of both. I try to keep them as long as possible, but they take up space. Sometimes it makes sense to recycle parts, though it’s not always easy.

I still have my first robots from 1992, but many are stored in crates. They’re not decorations around my house. And many don’t work anymore; they’d need serious upgrades to function again.

Q: Finally, what advice would you give to young people like me who are just starting robotic art?

Vorn: Keep doing it. Do not make things because others want you to. Make what you want to make.

There is no formula for success. It is unpredictable. When I started, there was less competition but also fewer examples. Now it is different, harder in one way and easier in another.

Do not get stuck on one project. Some ideas will not work, and that is fine. Keep moving and keep generating ideas. Persistence is the most important thing.

Closing Reflection

Interviewing Bill Vorn showed me how engineering and art can reinforce each other. As captain of FIRST Robotics Team 7520, I spend a lot of time thinking about efficiency, design, and performance on the competition field. Talking with him reminded me that machines are not only technical systems but also creative instruments. What gives robotics power is not just precision or reliability but the ability to spark emotion, curiosity, and imagination.

For me, engineering is the direction I want to pursue, but I see art as the foundation of creativity and problem-solving in every project. Art shapes the way I think about design, how I respond to glitches, and how I imagine what machines could do beyond their immediate function. This conversation reinforced that robotics is not just about control and optimization. It is also about openness, experimentation, and creating experiences that connect with people.

For more about Bill Vorn visit: https://billvorn.concordia.ca/menuall.html